In a valley that once shimmered with wheat and riverlight, a council of Peacekeepers arrived. They wore robes of ivory and gold, embroidered with doves and suns, and they spoke with honeyed tongues about “a new dawn for all.” The people, weary from years of small wars and quiet hungers, welcomed them as saviors.

The Peacekeepers built a pavilion in the center of the village, tall and white as a bone. They gave speeches about unity beneath fluttering banners, and each word shimmered like a prayer. But when the farmers asked for seeds, the Peacekeepers offered only songs. When the stonemasons asked for tools to rebuild the bridge, the Peacekeepers handed them scrolls of promises.

Still, the people clapped and smiled. They wanted to believe that peace was a thing that could be spoken into being.

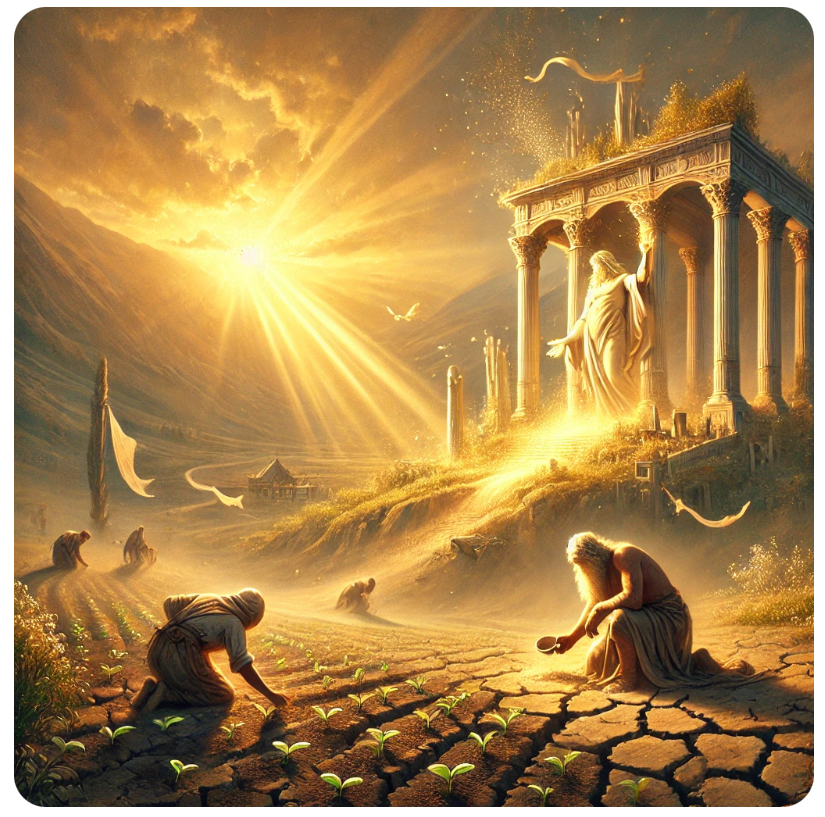

Then came a season of drought. The fields cracked, the river thinned to a trickle, and the pavilion began to sink in the soft dust. The Peacekeepers kept smiling, their robes clean, their hands empty. One night, the youngest villager—a girl who had never seen the river full—asked them,

“Where do you plant your peace?”

The Peacekeepers looked at one another, confused. They had no gardens, no calluses, no scars. Only speeches.

So the villagers began to work without them. They carried water in hollowed gourds, dug furrows, shared crusts of bread, and learned again how to live shoulder to shoulder. The pavilion collapsed behind them, its banners shredded into rags that fluttered like pale ghosts.

When the next spring came, green returned—not from the words of the Peacekeepers, but from the cracked hands of those who stayed to tend the soil.

“Peace spoken without labor is a mirage; true peace grows only where hands have touched the earth.”

Leave a comment