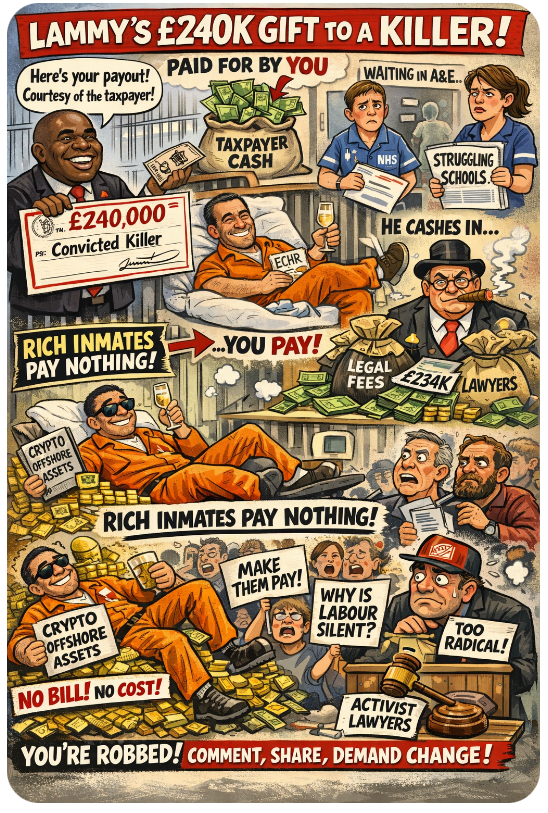

The headline is unavoidable, because the outcome is unavoidable.

A convicted Islamist extremist who shot two men execution-style, took a prison officer hostage, and demanded the release of a hate preacher, has now secured a £240,000 payout linked directly to the application of the European Convention on Human Rights.

That decision was signed off by David Lammy, Labour’s Justice Secretary.

Let’s be precise about what happened — and why it matters.

What Was Paid — and Why the Figure Is £240,000

The government agreed to:

- £7,500 in compensation paid directly to Fuad Awale

- £234,000 in legal costs, funded by the taxpayer

The total — £240,000 — is not a media exaggeration. It is the combined financial consequence of a human-rights ruling against the state.

Awale remains in prison, serving a life sentence with a minimum term of 38 years, but the payment is real, immediate, and borne entirely by the public.

Why the Court Ruled in His Favour

Awale was held in a special separation unit — designed to prevent:

- harm to prison officers

- coordination with other extremists

- radicalisation inside the prison estate

He argued that this segregation breached Article 8 of the European Convention on Human Rights, claiming it interfered with his “private life” and contributed to depression.

The High Court agreed.

Notably, the court was told Awale had requested association with the Islamist murderers of Lee Rigby — a request denied on counter-terrorism grounds. That denial formed part of the basis of his claim.

In effect, the state was punished financially for prioritising prison safety over prisoner association.

The Core Problem: Liability Without Responsibility

This case exposes a fundamental imbalance.

The state is held financially liable for restricting a dangerous extremist —

but the extremist bears no financial liability for:

- his crimes

- his incarceration

- the security burden he imposes

- the legal costs of his own litigation

That imbalance is not required by nature. It is a policy choice.

There is no principled reason why prisoners with access to funds — or external financial backing — should not be liable for the costs they generate, including:

- incarceration

- specialist security regimes

- unsuccessful or marginal litigation

Yet no such reform is being rushed through Parliament.

Why Isn’t Prisoner Cost-Liability Being Legislated?

If the government can legislate emergency measures for:

- public order

- immigration control

- national security

Then it can legislate to ensure that those who endanger society do not externalise all costs onto society.

The silence on this question is telling.

Instead, ministers speak vaguely about “reviewing frameworks” while approving settlements that reinforce the incentive structure that produced the claim in the first place.

The Public Impact: Trust, Safety, and Moral Clarity

Most voters will not parse Article 8 jurisprudence.

They will see:

- a violent Islamist extremist

- housed in high-security conditions for good reason

- receiving compensation

- while frontline public servants face risk with limited protection

They will ask a simple question:

Who is this system actually designed to protect?

When human-rights law appears to reward the most dangerous individuals while ignoring the moral weight of their actions, public trust collapses — and with it, respect for the law itself.

This Was Avoidable

This outcome was not inevitable.

It is the product of:

- failure to draft segregation laws robustly

- failure to anticipate litigation risk

- failure to rebalance rights with responsibility

- failure to act before courts force the issue

If Labour does not close this gap, others will — and not delicately.

Final Thought

A legal system that cannot safely segregate violent extremists without paying them is not humane — it is incoherent.

And every time the taxpayer is made to fund that incoherence, public confidence erodes a little further.

That is the real cost of this £240,000 decision.

Leave a comment