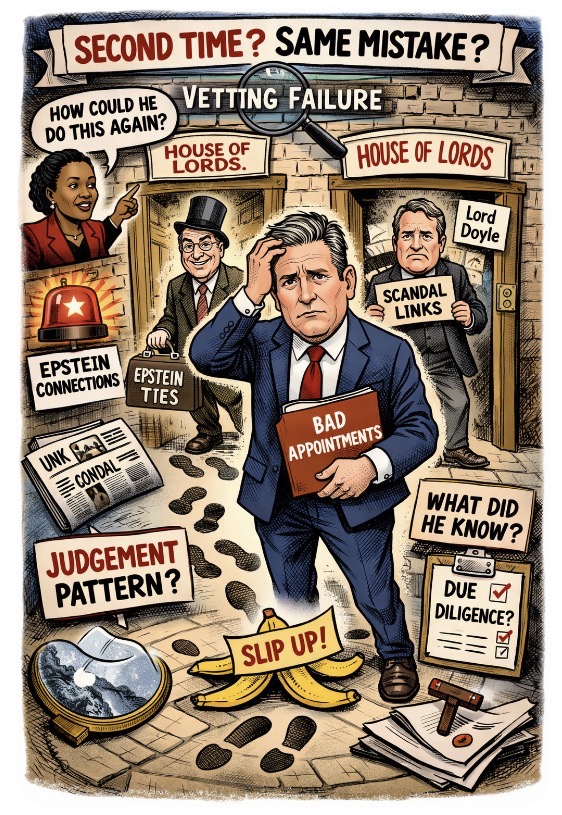

When a prime minister makes one controversial appointment, they can argue miscalculation. When it happens twice, the issue stops being optics and becomes judgment.

That is the problem facing Keir Starmer.

Following the earlier furore over Lord Peter Mandelson, the appointment of Matthew Doyle to the House of Lords has reopened the same wound: what due diligence was carried out, what was known, and why proceed if there was foreseeable reputational risk?

Doyle, a former senior aide, has since been suspended from the Labour Party whip after scrutiny of his past association with an individual convicted of child sex offences. Opposition figures, including Kemi Badenoch, have framed this not as an isolated lapse but as evidence of a recurring pattern.

That framing is politically potent — and difficult to dismiss.

The Core Question: What Was Known?

The public is not primarily asking whether Doyle committed wrongdoing. They are asking something more fundamental:

- What did Downing Street know?

- When did it know it?

- Why was the risk deemed acceptable?

In high office, association risk is not a trivial matter. It is assessed precisely because leadership is not only about legality but about credibility. A prime minister who brands himself as serious, forensic and disciplined cannot afford to appear casual about reputational exposure — particularly where safeguarding sensitivities are concerned.

If warning signs were known and discounted, that is a judgment failure.

If they were not known, that is a vetting failure.

Neither explanation inspires confidence.

Why “Twice” Matters

Politics tolerates single missteps. It rarely tolerates patterns.

The Mandelson episode was defended as an error of trust. This case now invites a harder interpretation: either the internal vetting process is structurally weak, or the threshold for acceptable controversy inside No.10 is misaligned with public expectation.

Either scenario damages authority.

In governance, appointments are not symbolic gestures — they are signals. They communicate standards. They tell the country what risks leadership is willing to absorb.

When controversy clusters around the same category — associations with individuals linked to serious criminality — the issue stops being partisan theatre. It becomes about calibration of judgment at the top.

The Political Cost

The danger for Starmer is not merely opposition attack lines. It is erosion of the competence narrative that carried him to power.

His brand has been built on seriousness, prosecutorial rigour, and ethical reset. Repeated controversies around appointments undermine that positioning far more than a policy disagreement ever could.

The public does not expect perfection.

It does expect pattern recognition.

If a mistake has already burned you once, repeating it looks less like misfortune and more like either overconfidence or insularity.

The Larger Issue

This is not about whether Doyle deserves personal condemnation. It is about whether a prime minister demonstrates anticipatory judgment — the ability to foresee political, ethical and reputational consequences before they land.

Leadership is tested not by how loudly it defends decisions, but by how carefully those decisions are made in the first place.

The question hanging over Downing Street is simple and unavoidable:

If this was foreseeable, why proceed?

And if it was not foreseeable, who is responsible for ensuring it is next time?

Until that is answered convincingly, the issue will not be the individual appointment — it will be the pattern.

Leave a comment