🤖⚖️🔥When the state starts whispering, “The AI made the recommendation,” it sounds modern. Efficient. Almost inevitable. If algorithms are being used in policing or immigration, surely they’ve been rebuilt from the silicon up—serious code for serious consequences.

Except… they usually haven’t.

Governments don’t demolish and reconstruct language models from scratch like they’re building a new courthouse. They adapt them. Fine-tune them. Wrap them in policy layers. Bolt on guardrails. Feed them case law. Restrict them to classification, summarisation, or risk scoring. The engine remains probabilistic; the paint job becomes bureaucratic.

And suddenly, a general-purpose machine begins to look like an institutional authority.

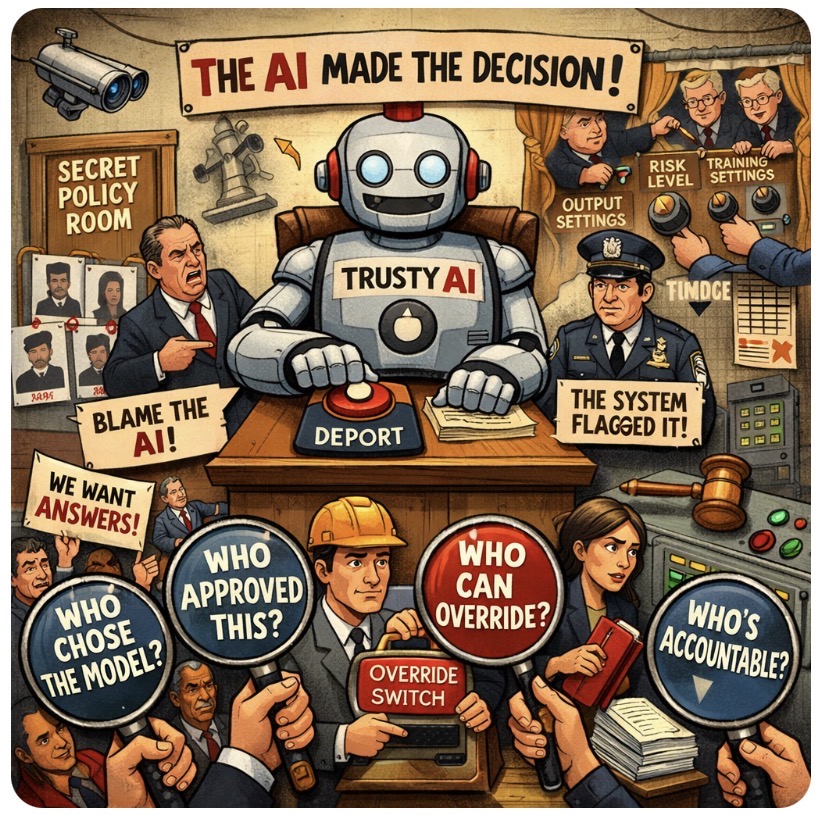

🎭 The Great Disappearing Decision-Maker

Here’s the sleight of hand: once embedded in official workflows, trained on departmental documents, and stamped with procedural approval, the system feels official. It speaks the language of policy. It cites guidance. It produces outputs formatted like conclusions.

But formatting is not legitimacy.

The model did not:

- Choose its objectives

- Define its risk thresholds

- Select its training corpus

- Approve its operational deployment

- Decide its outputs would carry weight

People did.

Yet the phrasing shifts. “The AI flagged the case.” “The system assessed the risk.” “The model recommended removal.”

Notice how the verbs quietly migrate from humans to software. 🫥

That linguistic pivot matters. Because once agency appears to move, accountability can blur.

Fine-tuning on immigration case law does not grant constitutional authority. Embedding a model in policing workflows does not imbue it with moral judgment. Adjusting training data does not alter the system’s nature: it remains a probabilistic engine operating within parameters chosen upstream.

Customisation can improve performance. It cannot inherit responsibility.

High-stakes public decisions absolutely require contextual engineering—bias mitigation, transparency, audit trails, validation against real cases. Specialisation is not optional; it’s governance 101. But governance does not end at deployment.

The real questions live before the prompt is ever typed:

- Who selected the model?

- Who validated it?

- Who approved its operational use?

- Who defined when its recommendation carries weight?

- Who can override it—and how easily?

These are not footnotes. They are the architecture of accountability.

When a department says, “The AI made this recommendation,” what it often means is: we configured a probabilistic system within constraints we designed, and we chose to rely on it.

The machine didn’t move the lever. It was installed next to it.

And no amount of fine-tuning converts software into a sovereign decision-maker. ⚙️👑

🔍 Challenges 🔍

If AI systems are shaping decisions about liberty, borders, or policing, should departments be legally required to name the human authority behind every automated recommendation?

Is “the system flagged it” acceptable language—or a convenient fog machine?

Jump into the blog comments (not just social media 👀). Bring your sharpest arguments. Question the euphemisms. Demand clarity. 💬🔥

👇 Comment. Like. Share.

The most incisive takes will be featured in the next issue of the magazine. 📰✨

Leave a comment